Category:NMR: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (8 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Nuclear magnetic resonance''' (NMR) spectroscopy is a highly sensitive technique for probing the atomic-scale structure of molecules, liquids, and solids. However, directly extracting structural information from NMR spectra is often challenging. Consequently, ''ab-initio'' quantum mechanical simulations, such as those performed using VASP, play a crucial role in accurately linking NMR spectra to atomic-scale structural properties. | |||

This page presents an overview of nuclear-electron interactions that can be computed and are relevant to interpret NMR spectra. | |||

==Chemical shielding== | |||

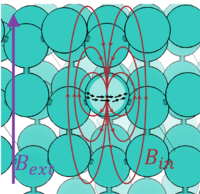

[[File:Chemical_shielding.png|200px|thumb|The external magnetic field '''B'''''<sub>ext</sub>'' (purple) induces currents in the electrons in atoms. These NMR response currents (black arrows) in turn induce an opposing magnetic field '''B'''''<sub>in</sub>'' (red), reducing the magnetic field at the position of the nucleus, effectively shielding the nucleus from '''B'''''<sub>ext</sub>''.]] The effective B-field felt by a nucleus with finite nuclear spin is related to the applied B field via the chemical shielding tensor. The applied B-field induces a para- and diamagnetic NMR response current in the electrons and screens the nucleus with an induced B-field that follows from the Biot-Savart law, c.f. figure. The chemical shift is the difference in chemical shielding σ relative to a reference σ<sub>ref</sub>. | |||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

\delta_{ij} = \sigma_{ij}^{\mathrm{ref}} - \sigma_{ij}. | |||

</math> | |||

\delta_{ij} | |||

</math> | |||

VASP can efficiently compute electronic properties in bulk systems thanks to the [[projector-augmented wave]] (PAW) method which takes advantage of [[pseudopotentials]] and a [[:Category:Pseudopotentials#Theory|frozen core approximation]]. However, the [[PAW formalism|standard PAW transformation]] does not fully account for how the gauge field <math>A</math> interacts with the reconstructed wavefunctions in the augmentation regions (near atomic cores). Thus, NMR calculations ({{TAGO|LCHIMAG|True}}) are based on an extended version of the [[PAW method]], the gauge-invariant PAW (GIPAW) method{{Cite|pickard:prb:2001}}{{Cite|yates:prb:2007}} that properly ensures the gauge invariance. The NMR currents ({{TAG|WRT_NMRCUR}}) are computed using linear response theory. | |||

* Learn [[Calculating the chemical shieldings|how to calculate the chemical shielding]]. | |||

<div style="clear:both;"></div> | |||

=== Nuclear-independent chemical shielding === | |||

Nuclear-independent chemical shielding (NICS) is a computational method used to quantify aromaticity in molecules by calculating the magnetic shielding at a virtual point (not at a nucleus) in space, typically at the center of a ring or above it. See {{TAG|NUCIND}} for more information. | |||

==Magnetic susceptibility== | ==Magnetic susceptibility== | ||

The magnetic susceptibility <math>\chi</math> is | The macroscopic magnetic susceptibility <math>\chi</math> is defined by {{Cite|mauri:louie:1996}} | ||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

\textbf{ | \textbf{B}_{\textrm{in}}^{(1)}(\textbf{G}=0) = \frac{8 \pi}{3} \chi \textbf{B}_{ext}, | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

where <math>\ | where <math>\textbf{B}_{ext}</math> is the external magnetic field and <math>\textbf{B}_{\textrm{in}}^{(1)}</math> is the induced magnetic field. This must be taken into account for the chemical shielding as a G=0 contribution. | ||

\textbf{B} | |||

</math> | |||

It is calculated within linear response theory ({{TAGO|LCHIMAG|True}}), where a key variable ''Q<sub>ij</sub>'' is approximated in two ways. The so-called ''pGv'' approximation is used by default {{Cite|yates:prb:2007}}, where ''p'' is momentum, ''v'' is velocity, and ''G'' is a Green's function. An alternative approach, the ''vGv'' approximation is available to calculate the susceptibility {{Cite|avezac:prb:2007}}. See {{TAG|LVGVCALC}} and {{TAG|LVGVAPPL}} to control the approximation. | |||

* Learn [[Calculating the magnetic susceptibility|how to perform a magnetic susceptibility calculation.]] | |||

<div style="clear:both;"></div> | |||

==Quadrupolar nuclei - electric field gradient== | ==Quadrupolar nuclei - electric field gradient== | ||

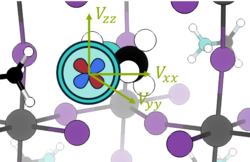

[[File:Quadrupolar_efg.png| | [[File:Quadrupolar_efg.png|250px|thumb|The quadrupolar electric field of a nitrogen nucleus coupling to electric field gradient ''V'' in MAPbI3 (methyl ammonium lead (III) iodide)]] | ||

Nuclei with '''I''' > ± ½ have | Nuclei with '''I''' > ± ½ have a non-zero electric field gradient (EFG) and an electronic quadrupolar moment. The electric quadrupolar moment couples with the EFG and so the chemical environment of the nucleus may be probed using nuclear quadrupole resonance (NQR) {{Cite|nqr:web}} (sometimes called zero-field NMR spectroscopy). The EFG is the second derivative of the potential <math>V</math>: | ||

<math> | :<math> | ||

V_{ij} = \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial x_i \partial x_j} | V_{ij} = \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial x_i \partial x_j} | ||

</math> | </math>, | ||

which is a sum of three parts along the Cartesian ''i'',''j'' axes: | |||

:<math> | |||

V_{i,j} = \tilde{V}_{i,j} -\tilde{V}_{i,j}^1 + V_{i,j}^1 | |||

</math> | |||

<math> | where <math>\tilde{V}_{i,j}</math> is the plane-wave part of the AE potential, <math>\tilde{V}_{i,j}^1</math> is the one-center expansion of the pseudopotential method, and <math>V_{i,j}^1</math> is the one-center expansion of the AE potential. | ||

</math> | |||

In VASP, the EFG is calculated using the {{TAG|LEFG}} tag. The commonly reported nuclear quadrupolar coupling constant ''C<sub>q</sub>'' is then printed using isotope-specific quadrupole moment defined using {{TAG|QUAD_EFG}} {{Cite|petrilli:prb:1998}}. | |||

* Learn [[Calculating the electric field gradient|how to perform an electric field gradient calculation]]. | |||

<div style="clear:both;"></div> | |||

==Hyperfine coupling== | ==Hyperfine coupling== | ||

[[File:Hyperfine_coupling.png| | [[File:Hyperfine_coupling.png|250px|thumb|Hyperfine coupling between the nuclear spin and the electronic spin of the unpaired electron at a nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center in diamond.]] | ||

The hyperfine tensor <math>A^I</math> describes the interaction between a nuclear spin <math>S^I</math> and the electronic spin distribution <math>S^e</math>. In most cases associated with a paramagnetic defect state measureable by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) {{Cite|weil:bolton:2007}}: | |||

:<math> | |||

E=\sum_{ij} S^e_i A^I_{ij} S^I_j. | |||

</math> | |||

The hyperfine tensor | The hyperfine tensor is split into two terms, isotropic (or Fermi contact) <math>A^I_{iso}</math> and anisotropic (or dipolar contributions) <math>A^I_{ani}</math>: | ||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

A^I_{i,j} = (A^I_{iso})_{i,j} + (A^I_{ani})_{i,j}. | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

The hyperfine tensor | <math>A^I_{iso}</math> is calculated based on the spin-density{{Cite|szasz:prb:2013}} and <math>A^I_{ani}</math> is calculated based on the dipolar-dipolar contribution terms <math>W_{i,j}(\textbf{R})</math>. The hyperfine tensor calculation itself is defined using {{TAGO|LHYPERFINE|True}}. Both the Fermi contact and dipolar contribution terms are related to the nuclear gyromagnetic moment γ, which are controlled by setting {{TAG|NGYROMAG}}. | ||

* Learn [[Calculating the hyperfine coupling constant|how to perform a hyperfine coupling calculation.]] | |||

* | <div style="clear:both;"></div> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

[[Category:Linear response]] | [[Category:Linear response]][[Category:Magnetism]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:35, 10 March 2025

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a highly sensitive technique for probing the atomic-scale structure of molecules, liquids, and solids. However, directly extracting structural information from NMR spectra is often challenging. Consequently, ab-initio quantum mechanical simulations, such as those performed using VASP, play a crucial role in accurately linking NMR spectra to atomic-scale structural properties.

This page presents an overview of nuclear-electron interactions that can be computed and are relevant to interpret NMR spectra.

Chemical shielding

The effective B-field felt by a nucleus with finite nuclear spin is related to the applied B field via the chemical shielding tensor. The applied B-field induces a para- and diamagnetic NMR response current in the electrons and screens the nucleus with an induced B-field that follows from the Biot-Savart law, c.f. figure. The chemical shift is the difference in chemical shielding σ relative to a reference σref.

VASP can efficiently compute electronic properties in bulk systems thanks to the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method which takes advantage of pseudopotentials and a frozen core approximation. However, the standard PAW transformation does not fully account for how the gauge field interacts with the reconstructed wavefunctions in the augmentation regions (near atomic cores). Thus, NMR calculations (LCHIMAG = True) are based on an extended version of the PAW method, the gauge-invariant PAW (GIPAW) method[1][2] that properly ensures the gauge invariance. The NMR currents (WRT_NMRCUR) are computed using linear response theory.

Nuclear-independent chemical shielding

Nuclear-independent chemical shielding (NICS) is a computational method used to quantify aromaticity in molecules by calculating the magnetic shielding at a virtual point (not at a nucleus) in space, typically at the center of a ring or above it. See NUCIND for more information.

Magnetic susceptibility

The macroscopic magnetic susceptibility is defined by [3]

where is the external magnetic field and is the induced magnetic field. This must be taken into account for the chemical shielding as a G=0 contribution.

It is calculated within linear response theory (LCHIMAG = True), where a key variable Qij is approximated in two ways. The so-called pGv approximation is used by default [2], where p is momentum, v is velocity, and G is a Green's function. An alternative approach, the vGv approximation is available to calculate the susceptibility [4]. See LVGVCALC and LVGVAPPL to control the approximation.

Quadrupolar nuclei - electric field gradient

Nuclei with I > ± ½ have a non-zero electric field gradient (EFG) and an electronic quadrupolar moment. The electric quadrupolar moment couples with the EFG and so the chemical environment of the nucleus may be probed using nuclear quadrupole resonance (NQR) [5] (sometimes called zero-field NMR spectroscopy). The EFG is the second derivative of the potential :

- ,

which is a sum of three parts along the Cartesian i,j axes:

where is the plane-wave part of the AE potential, is the one-center expansion of the pseudopotential method, and is the one-center expansion of the AE potential.

In VASP, the EFG is calculated using the LEFG tag. The commonly reported nuclear quadrupolar coupling constant Cq is then printed using isotope-specific quadrupole moment defined using QUAD_EFG [6].

Hyperfine coupling

The hyperfine tensor describes the interaction between a nuclear spin and the electronic spin distribution . In most cases associated with a paramagnetic defect state measureable by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) [7]:

The hyperfine tensor is split into two terms, isotropic (or Fermi contact) and anisotropic (or dipolar contributions) :

is calculated based on the spin-density[8] and is calculated based on the dipolar-dipolar contribution terms . The hyperfine tensor calculation itself is defined using LHYPERFINE = True. Both the Fermi contact and dipolar contribution terms are related to the nuclear gyromagnetic moment γ, which are controlled by setting NGYROMAG.

References

- ↑ C. J. Pickard and F. Mauri, All-electron magnetic response with pseudopotentials: NMR chemical shifts, Phys. Rev. B 63, 245101 (2001).

- ↑ a b J. R. Yates, C. J. Pickard, and F. Mauri, Calculation of NMR chemical shifts for extended systems using ultrasoft pseudopotentials, Phys. Rev. B 76, 024401 (2007).

- ↑ F. Mauri, S. G. Louie, Magnetic Susceptibility of Insulators from First Principles, Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4246 (1996).

- ↑ M. d'Avezac, N. Marzari, and F. Mauri, Spin and orbital magnetic response in metals: Susceptibility and NMR shifts, Phys. Rev. B 76, 165122 (2007).

- ↑ Nuclear quadrupole resonance, www.wikipedia.org (2025)

- ↑ H. M. Petrilli, P. E. Blöchl, P. Blaha, and K. Schwarz, Electric-field-gradient calculations using the projector augmented wave method, Phys. Rev. B 57, 14690 (1998).

- ↑ J. Weil and J. Bolton, Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Elementary Theory and Practical Applications, (2007).

- ↑ K. Szasz, T. Hornos, M. Marsman, and A. Gali, Hyperfine coupling of point defects in semiconductors by hybrid density functional calculations: The role of core spin polarization, Phys. Rev. B, 88, 075202 (2013).

Pages in category "NMR"

The following 14 pages are in this category, out of 14 total.